string Type

A string is a variable-length sequence of characters. To use the string type, we must include the string header. Because it is part of the library, string is defined in the std namespace. Our examples assume the following code:

#include <string>

using std::string;

This section describes the most common string operations; § 9.5 (p. 360) will cover additional operations.

In addition to specifying the operations that the library types provide, the standard also imposes efficiency requirements on implementors. As a result, library types are efficient enough for general use.

strings

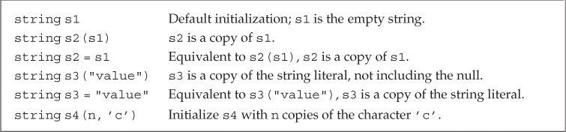

Each class defines how objects of its type can be initialized. A class may define many different ways to initialize objects of its type. Each way must be distinguished from the others either by the number of initializers that we supply, or by the types of those initializers. Table 3.1 lists the most common ways to initialize strings. Some examples:

string s1; // default initialization; s1 is the empty string

string s2 = s1; // s2 is a copy of s1

string s3 = "hiya"; // s3 is a copy of the string literal

string s4(10, 'c'); // s4 is cccccccccc

Table 3.1. Ways to Initialize a string

We can default initialize a string (§ 2.2.1, p. 44), which creates an empty string; that is, a string with no characters. When we supply a string literal (§ 2.1.3, p. 39), the characters from that literal—up to but not including the null character at the end of the literal—are copied into the newly created string. When we supply a count and a character, the string contains that many copies of the given character.

In § 2.2.1 (p. 43) we saw that C++ has several different forms of initialization. Using strings, we can start to understand how these forms differ from one another. When we initialize a variable using =, we are asking the compiler to copy initialize the object by copying the initializer on the right-hand side into the object being created. Otherwise, when we omit the =, we use direct initialization.

When we have a single initializer, we can use either the direct or copy form of initialization. When we initialize a variable from more than one value, such as in the initialization of s4 above, we must use the direct form of initialization:

string s5 = "hiya"; // copy initialization

string s6("hiya"); // direct initialization

string s7(10, 'c'); // direct initialization; s7 is cccccccccc

When we want to use several values, we can indirectly use the copy form of initialization by explicitly creating a (temporary) object to copy:

string s8 = string(10, 'c'); // copy initialization; s8 is cccccccccc

The initializer of s8—string(10, 'c')—creates a string of the given size and character value and then copies that value into s8. It is as if we had written

string temp(10, 'c'); // temp is cccccccccc

string s8 = temp; // copy temp into s8

Although the code used to initialize s8 is legal, it is less readable and offers no compensating advantage over the way we initialized s7.

strings

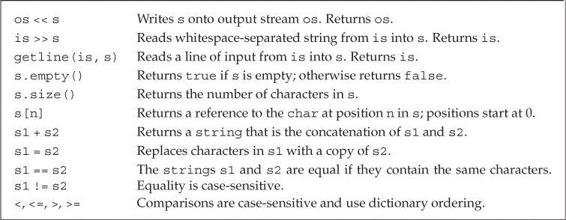

Along with defining how objects are created and initialized, a class also defines the operations that objects of the class type can perform. A class can define operations that are called by name, such as the isbn function of our Sales_item class (§ 1.5.2, p. 23). A class also can define what various operator symbols, such as << or +, mean when applied to objects of the class’ type. Table 3.2 (overleaf) lists the most common string operations.

stringsAs we saw in Chapter 1, we use the iostream library to read and write values of built-in types such as int, double, and so on. We use the same IO operators to read and write strings:

// Note: #include and using declarations must be added to compile this code

int main()

{

string s; // empty string

cin >> s; // read a whitespace-separated string into s

cout << s << endl; // write s to the output

return 0;

}

This program begins by defining an empty string named s. The next line reads the standard input, storing what is read in s. The string input operator reads and discards any leading whitespace (e.g., spaces, newlines, tabs). It then reads characters until the next whitespace character is encountered.

So, if the input to this program is Hello World! (note leading and trailing spaces), then the output will be Hello with no extra spaces.

Like the input and output operations on the built-in types, the string operators return their left-hand operand as their result. Thus, we can chain together multiple reads or writes:

string s1, s2;

cin >> s1 >> s2; // read first input into s1, second into s2

cout << s1 << s2 << endl; // write both strings

If we give this version of the program the same input, Hello World!, our output would be “HelloWorld!”

stringsIn § 1.4.3 (p. 14) we wrote a program that read an unknown number of int values. We can write a similar program that reads strings instead:

int main()

{

string word;

while (cin >> word) // read until end-of-file

cout << word << endl; // write each word followed by a new line

return 0;

}

In this program, we read into a string, not an int. Otherwise, the while condition executes similarly to the one in our previous program. The condition tests the stream after the read completes. If the stream is valid—it hasn’t hit end-of-file or encountered an invalid input—then the body of the while is executed. The body prints the value we read on the standard output. Once we hit end-of-file (or invalid input), we fall out of the while.

getline to Read an Entire LineSometimes we do not want to ignore the whitespace in our input. In such cases, we can use the getline function instead of the >> operator. The getline function takes an input stream and a string. This function reads the given stream up to and including the first newline and stores what it read—not including the newline—in its string argument. After getline sees a newline, even if it is the first character in the input, it stops reading and returns. If the first character in the input is a newline, then the resulting string is the empty string.

Like the input operator, getline returns its istream argument. As a result, we can use getline as a condition just as we can use the input operator as a condition (§ 1.4.3, p. 14). For example, we can rewrite the previous program that wrote one word per line to write a line at a time instead:

int main()

{

string line;

// read input a line at a time until end-of-file

while (getline(cin, line))

cout << line << endl;

return 0;

}

Because line does not contain a newline, we must write our own. As usual, we use endl to end the current line and flush the buffer.

The newline that causes

getlineto return is discarded; the newline is not stored in thestring.

string empty and size OperationsThe empty function does what one would expect: It returns a bool (§ 2.1, p. 32) indicating whether the string is empty. Like the isbn member of Sales_item (§ 1.5.2, p. 23), empty is a member function of string. To call this function, we use the dot operator to specify the object on which we want to run the empty function.

We can revise the previous program to only print lines that are not empty:

// read input a line at a time and discard blank lines

while (getline(cin, line))

if (!line.empty())

cout << line << endl;

The condition uses the logical NOT operator (the !

operator). This operator returns the inverse of the bool value of its operand. In this case, the condition is true if str is not empty.

The size member returns the length of a string (i.e., the number of characters in it). We can use size to print only lines longer than 80 characters:

string line;

// read input a line at a time and print lines that are longer than 80 characters

while (getline(cin, line))

if (line.size() > 80)

cout << line << endl;

string::size_type TypeIt might be logical to expect that size returns an int or, thinking back to § 2.1.1 (p. 34), an unsigned. Instead, size returns a string::size_type value. This type requires a bit of explanation.

The string class—and most other library types—defines several companion types. These companion types make it possible to use the library types in a machine-independent manner. The type size_type is one of these companion types. To use the size_type defined by string, we use the scope operator to say that the name size_type is defined in the string class.

Although we don’t know the precise type of string::size_type, we do know that it is an unsigned type (§ 2.1.1, p. 32) big enough to hold the size of any string. Any variable used to store the result from the string size operation should be of type string::size_type.

Admittedly, it can be tedious to type string::size_type. Under the new standard, we can ask the compiler to provide the appropriate type by using auto or decltype (§ 2.5.2, p. 68):

auto len = line.size(); // len has type string::size_type

Because size returns an unsigned type, it is essential to remember that expressions that mix signed and unsigned data can have surprising results (§ 2.1.2, p. 36). For example, if n is an int that holds a negative value, then s.size() < n will almost surely evaluate as true. It yields true because the negative value in n will convert to a large unsigned value.

You can avoid problems due to conversion between

unsignedandintby not usingints in expressions that usesize().

stringsThe string class defines several operators that compare strings. These operators work by comparing the characters of the strings. The comparisons are case-sensitive—upper- and lowercase versions of a letter are different characters.

The equality operators (== and !=) test whether two strings are equal or unequal, respectively. Two strings are equal if they are the same length and contain the same characters. The relational operators <, <=, >, >= test whether one string is less than, less than or equal to, greater than, or greater than or equal to another. These operators use the same strategy as a (case-sensitive) dictionary:

1. If two

strings have different lengths and if every character in the shorterstringis equal to the corresponding character of the longerstring, then the shorterstringis less than the longer one.

2. If any characters at corresponding positions in the two

strings differ, then the result of thestringcomparison is the result of comparing the first character at which thestrings differ.

As an example, consider the following strings:

string str = "Hello";

string phrase = "Hello World";

string slang = "Hiya";

Using rule 1, we see that str is less than phrase. By applying rule 2, we see that slang is greater than both str and phrase.

stringsIn general, the library types strive to make it as easy to use a library type as it is to use a built-in type. To this end, most of the library types support assignment. In the case of strings, we can assign one string object to another:

string st1(10, 'c'), st2; // st1 is cccccccccc; st2 is an empty string

st1 = st2; // assignment: replace contents of st1 with a copy of st2

// both st1 and st2 are now the empty string

stringsAdding two strings yields a new string that is the concatenation of the left-hand followed by the right-hand operand. That is, when we use the plus operator (+) on strings, the result is a new string whose characters are a copy of those in the left-hand operand followed by those from the right-hand operand. The compound assignment operator (+=) (§ 1.4.1, p. 12) appends the right-hand operand to the left-hand string:

string s1 = "hello, ", s2 = "world\n";

string s3 = s1 + s2; // s3 is hello, world\n

s1 += s2; // equivalent to s1 = s1 + s2

stringsAs we saw in § 2.1.2 (p. 35), we can use one type where another type is expected if there is a conversion from the given type to the expected type. The string library lets us convert both character literals and character string literals (§ 2.1.3, p. 39) to strings. Because we can use these literals where a string is expected, we can rewrite the previous program as follows:

string s1 = "hello", s2 = "world"; // no punctuation in s1 or s2

string s3 = s1 + ", " + s2 + '\n';

When we mix strings and string or character literals, at least one operand to each + operator must be of string type:

string s4 = s1 + ", "; // ok: adding a string and a literal

string s5 = "hello" + ", "; // error: no string operand

string s6 = s1 + ", " + "world"; // ok: each + has a string operand

string s7 = "hello" + ", " + s2; // error: can't add string literals

The initializations of s4 and s5 involve only a single operation each, so it is easy to see whether the initialization is legal. The initialization of s6 may appear surprising, but it works in much the same way as when we chain together input or output expressions (§ 1.2, p. 7). This initialization groups as

string s6 = (s1 + ", ") + "world";

The subexpression s1 + ", " returns a string, which forms the left-hand operand of the second + operator. It is as if we had written

string tmp = s1 + ", "; // ok: + has a string operand

s6 = tmp + "world"; // ok: + has a string operand

On the other hand, the initialization of s7 is illegal, which we can see if we parenthesize the expression:

string s7 = ("hello" + ", ") + s2; // error: can't add string literals

Now it should be easy to see that the first subexpression adds two string literals. There is no way to do so, and so the statement is in error.

For historical reasons, and for compatibility with C, string literals are not standard library

strings. It is important to remember that these types differ when you use string literals and librarystrings.

Exercises Section 3.2.2

Exercise 3.2: Write a program to read the standard input a line at a time. Modify your program to read a word at a time.

Exercise 3.3: Explain how whitespace characters are handled in the

stringinput operator and in thegetlinefunction.Exercise 3.4: Write a program to read two

strings and report whether thestrings are equal. If not, report which of the two is larger. Now, change the program to report whether thestrings have the same length, and if not, report which is longer.Exercise 3.5: Write a program to read

strings from the standard input, concatenating what is read into one largestring. Print the concatenatedstring. Next, change the program to separate adjacent inputstrings by a space.

string

Often we need to deal with the individual characters in a string. We might want to check to see whether a string contains any whitespace, or to change the characters to lowercase, or to see whether a given character is present, and so on.

One part of this kind of processing involves how we gain access to the characters themselves. Sometimes we need to process every character. Other times we need to process only a specific character, or we can stop processing once some condition is met. It turns out that the best way to deal with these cases involves different language and library facilities.

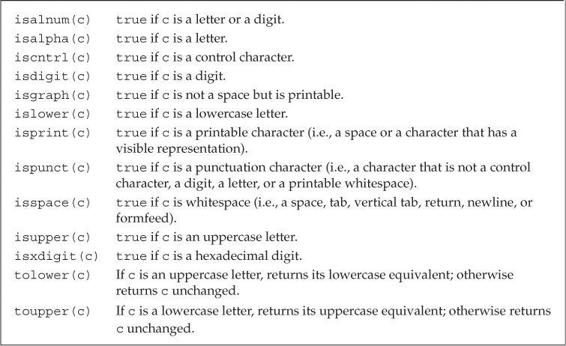

The other part of processing characters is knowing and/or changing the characteristics of a character. This part of the job is handled by a set of library functions, described in Table 3.3 (overleaf). These functions are defined in the cctype header.

In addition to facilities defined specifically for C++, the C++ library incorporates the C library. Headers in C have names of the form name

.h. The C++ versions of these headers are namedcname—they remove the.hsuffix and precede the name with the letterc. Thecindicates that the header is part of the C library.Hence,

cctypehas the same contents asctype.h, but in a form that is appropriate for C++ programs. In particular, the names defined in thecname headers are defined inside thestdnamespace, whereas those defined in the.hversions are not.Ordinarily, C++ programs should use the

cname versions of headers and not the name.hversions. That way names from the standard library are consistently found in thestdnamespace. Using the.hheaders puts the burden on the programmer to remember which library names are inherited from C and which are unique to C++.

forIf we want to do something to every character in a string, by far the best approach is to use a statement introduced by the new standard: the range for statement. This statement iterates through the elements in a given sequence and performs some operation on each value in that sequence. The syntactic form is

for (declaration : expression)

statement

where expression is an object of a type that represents a sequence, and declaration defines the variable that we’ll use to access the underlying elements in the sequence. On each iteration, the variable in declaration is initialized from the value of the next element in expression.

A string represents a sequence of characters, so we can use a string as the expression in a range for. As a simple example, we can use a range for to print each character from a string on its own line of output:

string str("some string");

// print the characters in str one character to a line

for (auto c : str) // for every char in str

cout << c << endl; // print the current character followed by a newline

The for loop associates the variable c with str. We define the loop control variable the same way we do any other variable. In this case, we use auto (§ 2.5.2, p. 68) to let the compiler determine the type of c, which in this case will be char. On each iteration, the next character in str will be copied into c. Thus, we can read this loop as saying, “For every character c in the string str,” do something. The “something” in this case is to print the character followed by a newline.

As a somewhat more complicated example, we’ll use a range for and the ispunct function to count the number of punctuation characters in a string:

string s("Hello World!!!");

// punct_cnt has the same type that s.size returns; see § 2.5.3 (p. 70)

decltype(s.size()) punct_cnt = 0;

// count the number of punctuation characters in s

for (auto c : s) // for every char in s

if (ispunct(c)) // if the character is punctuation

++punct_cnt; // increment the punctuation counter

cout << punct_cnt

<< " punctuation characters in " << s << endl;

The output of this program is

3 punctuation characters in Hello World!!!

Here we use decltype (§ 2.5.3, p. 70) to declare our counter, punct_cnt. Its type is the type returned by calling s.size, which is string::size_type. We use a range for to process each character in the string. This time we check whether each character is punctuation. If so, we use the increment operator (§ 1.4.1, p. 12) to add 1 to the counter. When the range for completes, we print the result.

for to Change the Characters in a stringIf we want to change the value of the characters in a string, we must define the loop variable as a reference type (§ 2.3.1, p. 50). Remember that a reference is just another name for a given object. When we use a reference as our control variable, that variable is bound to each element in the sequence in turn. Using the reference, we can change the character to which the reference is bound.

Suppose that instead of counting punctuation, we wanted to convert a string to all uppercase letters. To do so we can use the library toupper function, which takes a character and returns the uppercase version of that character. To convert the whole string we need to call toupper on each character and put the result back in that character:

string s("Hello World!!!");

// convert s to uppercase

for (auto &c : s) // for every char in s (note: c is a reference)

c = toupper(c); // c is a reference, so the assignment changes the char in s

cout << s << endl;

The output of this code is

HELLO WORLD!!!

On each iteration, c refers to the next character in s. When we assign to c, we are changing the underlying character in s. So, when we execute

c = toupper(c); // c is a reference, so the assignment changes the char in s

we’re changing the value of the character to which c is bound. When this loop completes, all the characters in str will be uppercase.

A range for works well when we need to process every character. However, sometimes we need to access only a single character or to access characters until some condition is reached. For example, we might want to capitalize only the first character or only the first word in a string.

There are two ways to access individual characters in a string: We can use a subscript or an iterator. We’ll have more to say about iterators in § 3.4 (p. 106) and in Chapter 9.

The subscript operator (the [ ]

operator) takes a string::size_type (§ 3.2.2, p. 88) value that denotes the position of the character we want to access. The operator returns a reference to the character at the given position.

Subscripts for strings start at zero; if s is a string with at least two characters, then s[0] is the first character, s[1] is the second, and the last character is in s[s.size() - 1].

The values we use to subscript a

stringmust be>= 0and< size().The result of using an index outside this range is undefined.

By implication, subscripting an empty

stringis undefined.

The value in the subscript is referred to as “a subscript” or “an index.” The index we supply can be any expression that yields an integral value. However, if our index has a signed type, its value will be converted to the unsigned type that string::size_type represents (§ 2.1.2, p. 36).

The following example uses the subscript operator to print the first character in a string:

if (!s.empty()) // make sure there's a character to print

cout << s[0] << endl; // print the first character in s

Before accessing the character, we check that s is not empty. Any time we use a subscript, we must ensure that there is a value at the given location. If s is empty, then s[0] is undefined.

So long as the string is not const (§ 2.4, p. 59), we can assign a new value to the character that the subscript operator returns. For example, we can capitalize the first letter as follows:

string s("some string");

if (!s.empty()) // make sure there's a character in s[0]

s[0] = toupper(s[0]); // assign a new value to the first character in s

The output of this program is

Some string

As a another example, we’ll change the first word in s to all uppercase:

// process characters in s until we run out of characters or we hit a whitespace

for (decltype(s.size()) index = 0;

index != s.size() && !isspace(s[index]); ++index)

s[index] = toupper(s[index]); // capitalize the current character

This program generates

SOME string

Our for loop (§ 1.4.2, p. 13) uses index to subscript s. We use decltype to give index the appropriate type. We initialize index to 0 so that the first iteration will start on the first character in s. On each iteration we increment index to look at the next character in s. In the body of the loop we capitalize the current letter.

The new part in this loop is the condition in the for. That condition uses the logical AND operator (the &&

operator). This operator yields true if both operands are true and false otherwise. The important part about this operator is that we are guaranteed that it evaluates its right-hand operand only if the left-hand operand is true. In this case, we are guaranteed that we will not subscript s unless we know that index is in range. That is, s[index] is executed only if index is not equal to s.size(). Because index is never incremented beyond the value of s.size(), we know that index will always be less than s.size().

When we use a subscript, we must ensure that the subscript is in range. That is, the subscript must be

>= 0and<thesize()of thestring. One way to simplify code that uses subscripts is always to use a variable of typestring::size_typeas the subscript. Because that type isunsigned, we ensure that the subscript cannot be less than zero. When we use asize_typevalue as the subscript, we need to check only that our subscript is less than value returned bysize().The library is not required to check the value of an subscript. The result of using an out-of-range subscript is undefined.

In the previous example we advanced our subscript one position at a time to capitalize each character in sequence. We can also calculate an subscript and directly fetch the indicated character. There is no need to access characters in sequence.

As an example, let’s assume we have a number between 0 and 15 and we want to generate the hexadecimal representation of that number. We can do so using a string that is initialized to hold the 16 hexadecimal “digits”:

const string hexdigits = "0123456789ABCDEF"; // possible hex digits

cout << "Enter a series of numbers between 0 and 15"

<< " separated by spaces. Hit ENTER when finished: "

<< endl;

string result; // will hold the resulting hexify'd string

string::size_type n; // hold numbers from the input

while (cin >> n)

if (n < hexdigits.size()) // ignore invalid input

result += hexdigits[n]; // fetch the indicated hex digit

cout << "Your hex number is: " << result << endl;

If we give this program the input

12 0 5 15 8 15

the output will be

Your hex number is: C05F8F

We start by initializing hexdigits to hold the hexadecimal digits 0 through F. We make that string const (§ 2.4, p. 59) because we do not want these values to change. Inside the loop we use the input value n to subscript hexdigits. The value of hexdigits[n] is the char that appears at position n in hexdigits. For example, if n is 15, then the result is F; if it’s 12, the result is C; and so on. We append that digit to result, which we print once we have read all the input.

Whenever we use a subscript, we should think about how we know that it is in range. In this program, our subscript, n, is a string::size_type, which as we know is an unsigned type. As a result, we know that n is guaranteed to be greater than or equal to 0. Before we use n to subscript hexdigits, we verify that it is less than the size of hexdigits.

Exercises Section 3.2.3

Exercise 3.6: Use a range

forto change all the characters in astringtoX.Exercise 3.7: What would happen if you define the loop control variable in the previous exercise as type

char? Predict the results and then change your program to use acharto see if you were right.Exercise 3.8: Rewrite the program in the first exercise, first using a

whileand again using a traditionalforloop. Which of the three approaches do you prefer and why?Exercise 3.9: What does the following program do? Is it valid? If not, why not?

string s;

cout << s[0] << endl;Exercise 3.10: Write a program that reads a string of characters including punctuation and writes what was read but with the punctuation removed.

Exercise 3.11: Is the following range

forlegal? If so, what is the type ofc?const string s = "Keep out!";

for (auto &c : s) { /* ... */ }